designer babies no one asked for: protein cryptography paper speedrun

cryptographers are finally getting around to answering our deepest, most pressing questions

but what if we used babies as encrypted storage format?[1]

i surely cannot imagine encoding dad-jokes in my future childrens' proteins.

but no one is actually talking about using babies as a substrate for cryptography (yet). a paper posted to IACR this week explores the idea of using proteins as an encrypted data storage format. we’re going to speedrun explain that paper.

thanks to Keoni Gandall for comments.

wat

okay so three big questions i had going in:

- is there some fancy steganographic key hiding that we could do with biology that we could not otherwise do?

- for example, there exists this quantum protocol for tamper-proof one-time-pad distribution, by pre-distributing qubits in superposition, then collapsing these to one-time-pad keys between sender and receiver[2]

- how efficiently could we possibly store (possibly encrypted) data in proteins, what’s our bit-density in amino-acids, and do we need to pay out the ass for encoding error-rates, and maybe error-correcting codes

- how far from reality are we really here: how expensive in time and dollars would it be to encode and decode

it turns out the answer is yes.

the paper only speaks to the first question, which is summarized in the next section; the the rest of this post is my rambling and back of the envelope math.

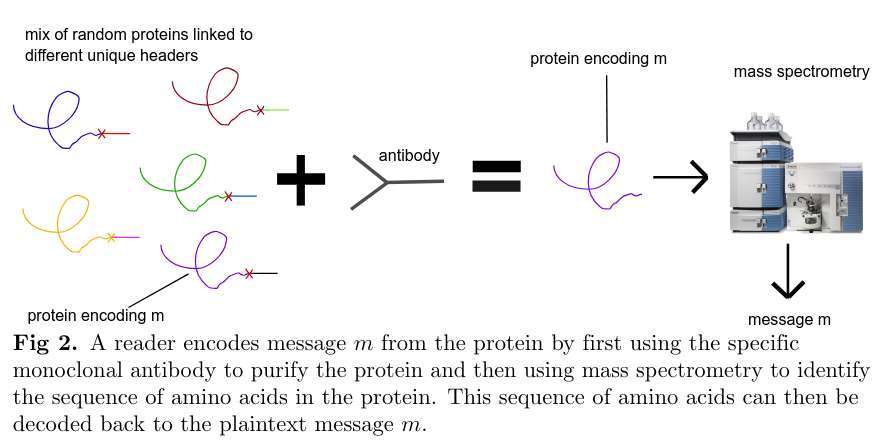

fancy steganography

the only known way to isolate a protein mixed with other proteins, is to purify the target protein using a monoclonal antibody (mAb), before sequencing it[3]. the adversary must know the correct mAb in advance to isolate the protein.[4]

that is, sequencing (encryption) a protein is easy, but synthesis (decryption) is hard and admits only one destructive attempt.

the authors further note that there is no known way to clone protein “in small amount”, which if possible, would allow for multiple synthesis attempts.

thus we get a basic idea why proteins might be well suited for cryptography; they have some convenient properties:

- uncloneability - can’t clone the ciphertext payload

- destructive sequencing - attempts to decrypt destroy the payload

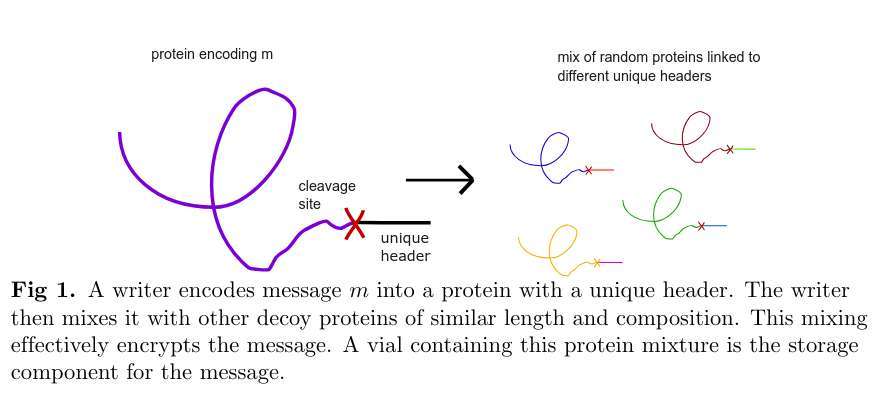

this gives us a basic idea for a symmetric encryption scheme: to encrypt: encode a message into a protein and tag the protein with a header that can be isolated by an mAb held by the receiver; then mix the message protein with other “decoy” proteins of similar length and composition.

to decrypt, isolate the protein with the corresponding mAb and synthesize it with mass spectrometry.

the authors term this the Miftah symmetric encryption scheme. we now set about to answer the question, but how impractical is this really?

how efficiently can we pack data in amino acids

let’s first not think about encryption at all, and just try to pack as much data as we can. proteins are made of strings of amino acids. there are 20 natural amino acids, upper bounding us to abt 4.32 bits of information per amino acid. mass spectrometry can be used to read the string of amino acids, destroying the string in the process.

we could try to encode arbitrary proteins from amino acids, but most would be unviable. claude estimates that of length 50 amino acid chains, only 1 in

if we take 160 bits in a length 50 protein at face value, we can try to compute for naive density of data.

mass spectrometry needs between 10^12 and 10^15 identical samples for reliable sequencing. amino acids weigh ~110 daltons. 50 AAs = 5500 daltons = 9.13 × 10^-21 grams. we get 160 bits / 9.13 × 10^-21 grams ≈ 1.75 × 10^22 bits/gram.

protein headers for the mAb to grab would be maybe 10-20 amino acids, about 25% overhead for headers, and we might also want to extend our proteins by another 25% to allow for error correcting codes.

supposing optimistically that we only need 10^12 replicas for mass spectrometry, we arrive at around 10^9 bits/gram, which would still be pretty ridiculously good, given that modern hard drives are on the order of 1 × 10^12 bits/gram for naive data storage.

for encryption, the paper doesn’t explore how many decoys would be necessary, but maybe about 100 decoy proteins to every one message protein would be sufficient. that further reduces our information density by another 10^2.

that brings our final estimate to around 1Mb/g for protein encrypted data, which is still pretty neat.

so, uh when should we expect this to become viable at cost?

but how expensive would it be to embed a dad joke in the proteins of my children

for encryption:

- protein synthesis ~$1k, multiplied by 100 decoys for security

- add ~$20k for sequencing a custom mAb

- this all would take on the order of 3 weeks to synthesize the proteins, and 3 months to produce the antibodies

but decryption is relatively cheap! on the order of $500 in 1-2 days for protein purification and another $200 in a few hours for mass spectrometry.

so, pretty practical. the future is here.

-

no one is asking this, the authors make did not mention babies once in their paper, but sure i guess we could do it

-

thor has extremely lossy understanding of quantum things, and makes only the weakest claim to have said this correctly

-

a note from Keoni Gandall: there are other ways to purify proteins; “you can purify proteins based on their size with columns and such, as well as methods that use salt (taking advantage of the solubility differences in different proteins)”

-

the paper does not answer the question of how large the key space of possible mAb’s is, but since spectrometry is destructive, the key space doesn’t need to be massive. thor estimate: since an mAb has about 120 amino acids in the variable region, with 20 possible amino acids, that the mAb key space is much larger than