What follows an introduction to the Stone Prover. Pebble Stark is my WIP re-implementation of the Stone Prover as a set of modular Rust libraries targeting web-assembly compilation, thereby enabling client-side proving (proving Cairo from a browser or phone). The target audience for this post are those familiar with verfiable computation at a high level, looking to learn more about the Stone Prover in particular. Thanks to StarkWare for supporting this work.

Background

The Stone Prover is a C++ implementation of a STARK[1] proving system developed by StarkWare. There are two architectural approaches for designing proving systems:

- Circuit DSL approaches like Plonky 2, Halo 2, and circom allow developers to lay out a circuit representing an arbitrary program, without an intermediate instruction-set representation. These libraries generally allow developers to achieve high levels of circuit performance, but typically offer very low-level developer experience. Circuits are also harder to audit for security and correctness.

- Virtual machine[2] approaches like Stone, Risc-0, and zkEVM construct circuit equivalents for each instruction in the target instruction set. Some zero knowledge virtual machines target existing instruction sets: Risc-0 and zkEVM target RISC-V and the EVM instruction sets respectively; while Stone was designed specifically to prove instances of Cairo Assembly (CASM), designed by the Starkware team for efficient STARK proving. Virtual machines effectively provide an abstraction layer over the the way that a circuit is laid out, allowing for better program modularity and auditability than writing a zk circuit directly.

The pipeline for producing a proof with Stone is as follows.

Diagram scaffold

- User writes Cairo program

- Compiles program to CASM (with what?)

- Proves CASM instance (with stone)

- For cost savings, SHARP aggregates multiple STARK proofs into a single proof - (cairo jobs) - aggregates jobs into a train--aggregated jobs

- starknet - produces cairo jobs for sharp to prove

- where the program is deployed ( on starknet )

- Ethereum chain verifies aggregated proof

Proving a Cairo Program

Given a program written in Cairo, the program is first compiled to the Sierra IR, then to CASM with the Cairo compiler. The Stone Prover executes the CASM program, generating a trace of its execution, and proves the correctness of that trace. The resultant proof may then be aggregated with other proofs, or submitted directly to a verifier.

In more detail, Stone executes the CASM program, taking snapshots of the program state after the execution of each instruction. The collection of these snapshots of the state of the program is called the trace, which is a sort of table describing the entire execution of the program. You may think of a the trace as describing collection of registers, loading and manipulating information in memory. That is, if we have 8 registers, and execute 200 instructions, the trace is said to have width 8, and height 200. The trace describes the program, but keep in mind that the goal is to prevent a cheating prover from lying about the program execution. Therefore, the proof should show that the trace is consistent with a set of constraints. The trace plus the constraints are called the arithmetization scheme. Stone, and STARKs in general, use an arithmetization scheme called Algebraic Intermediate Representation, AIR.

Now, that we have the AIR–the trace and constraints–we need to prove that the trace satisfies the constraints with FRI (Fast Reed-solomon IOPPs). Relative to the two other common proving schemes, KZG and IPA, FRI proofs employed in STARKs generate proofs quickly (the prover does less work), but generate larger proofs, on the order of 100kB. However, as we’ll see in the next step, there are tricks to amortize the cost of verifying larger proofs with recursion. You may think of FRI as a gadget for creating the proof that the trace satisfies the constraints.

That is, the Stone Prover:

- inputs a program consisting of CASM instructions

- executes the program to generate the trace

- lays out the trace in an AIR, representing the constraints between each row of the execution trace

- and finally, proves that the trace satisfies the constraints with FRI.

The Stone Prover’s work is done, but for the sake of completeness, we will briefly mention two further steps in the pipeline of proof generation: proof-aggregation, and verification.

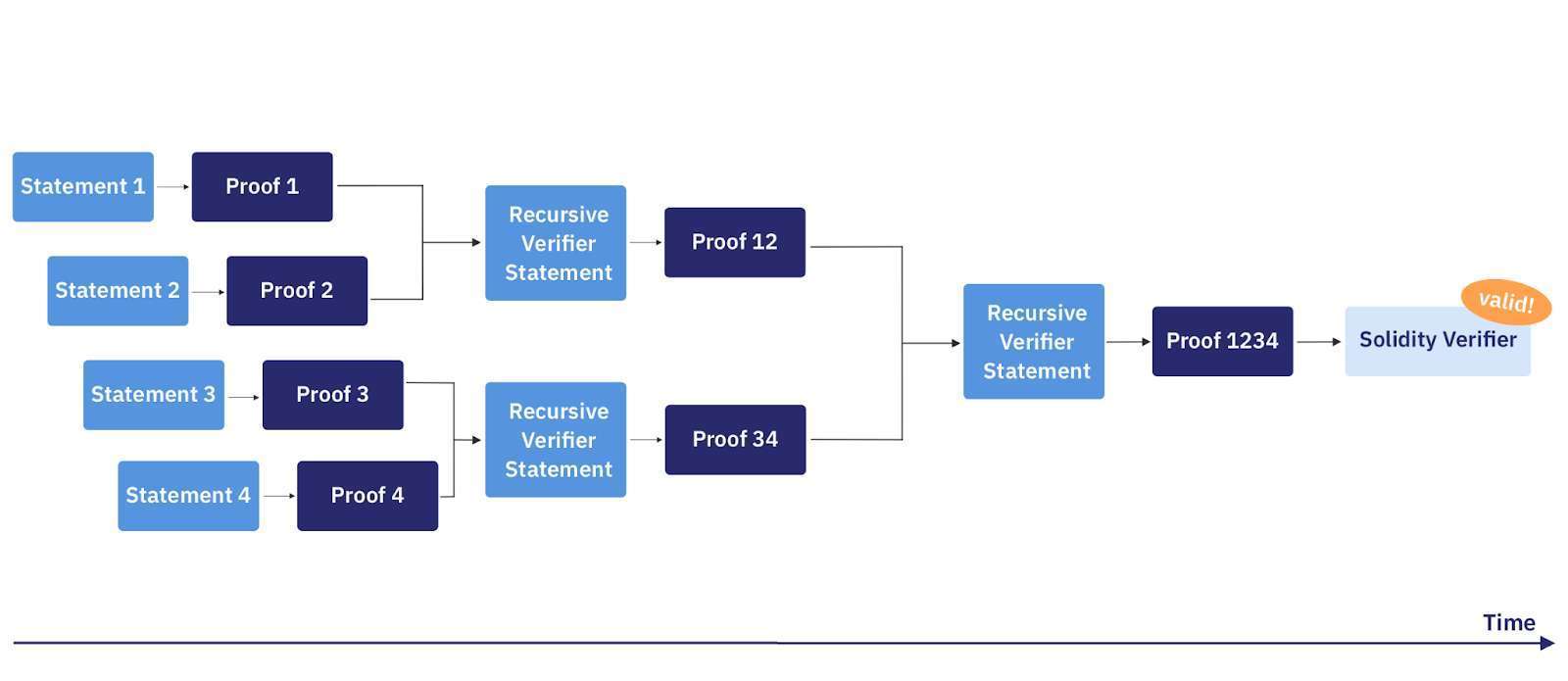

Now suppose we have a STARK proof, demonstrating the correct execution of some program. We could directly verify the STARK proof, but if the verifier must verify the proofs corresponding to more than one program, we can save the verifier work by combining the proofs in a clever way. Proof Aggregation is exactly this, a way to combine proofs together. The SHARP proof aggregator implements proof aggregation for Stone. Conveniently, aggregation of FRI proofs can be parallelized.

Proof aggregation batching proof instances; source

Proof aggregation batching proof instances; source

Finally, the proof is verified; verification performs the same algorithm regardless of whether the proof is aggregated. Recall that one of the goals of verifiable computation is that the verifier perform sub-linear work to verify the proof, relative to naively computing the program. That is, if the verifier would have perfomed

footnotes

-

Scalable Transparant ARguments of Knowledge (STARKs) are proof systems where (1) the prover time is at most quasilinear (at most

-

But what is a virtual machine? A virtual machine (VM) is really just a non-native instruction set, meaning that your machine can evaluate programs in an assembly language differing from it’s own. The two most common architectures are Intel x86 and ARM, and your system typically implements instructions at the hardware level for speed. Machines on these hardware architectures may still run programs targeting other instruction sets, by software emulation. That is, even though my machine runs Intel x86, I may run programs in ARM, EVM, or RISC-V via software emulation. The “virtual machine” is the component that does the software emulation. In the case of zkVMs, I may emulate the execution of a program in a particular VM that produces proofs of correct execution. Outside of the context of zkVMs, VMs are also used for server virtualization (VMware vSphere cloud-compute server), reproducible testing and development (Docker), and to run different operating systems on a single hardware platform.