What makes a game a “blockchain game”? A simple definition: some part of the state of the game is stored on a blockchain and is therefore publicly visible. Think chess or tic-tac-toe: each move is a state change on a publicly visible ledger. Compare this to games like League of Legends or Call of Duty, where the game state lives entirely on a private game server.

Suppose we wanted to store the entire game state on-chain. But then, every player would be able to see the entire “game board” and the position of every opposing player. For games like chess, that’s fine. But can we build a game with hidden information like Civilization where players have only a partial view of their environment and opponents?

The game Dark Forest is exactly that. By using zkSNARK cryptography (zero knowledge Succinct Non-interactive ARguments of Knowledge), the developers of Dark Forest have designed a universe and created a game where the state is completely stored on-chain. And yet each coordinate is hidden behind a hash that players may compute. This way all participants can explore and conquer a corner of the universe, and what they discover is consistent with what other participants see when they explore that region.

This article will focus on the game mechanics that the Dark Forest team were able to implement by applying SNARKs, and explore how these schemes push the limit of possible game interaction beyond the limits of prior art, such as commit-reveal schemes.

The Game, Succinctly

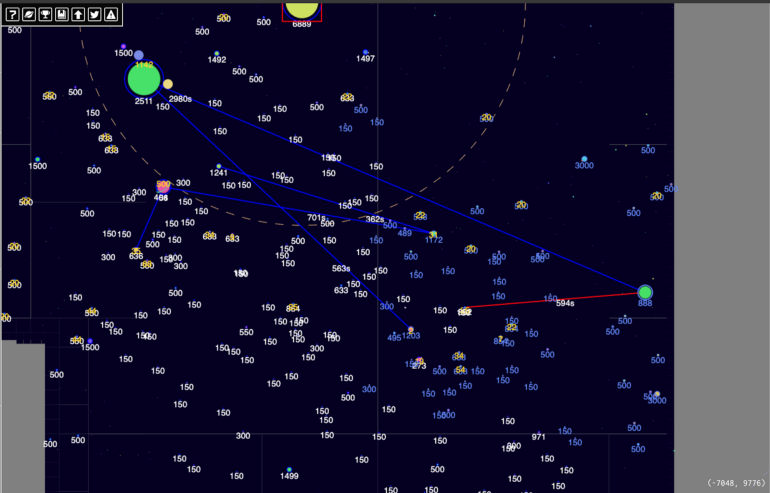

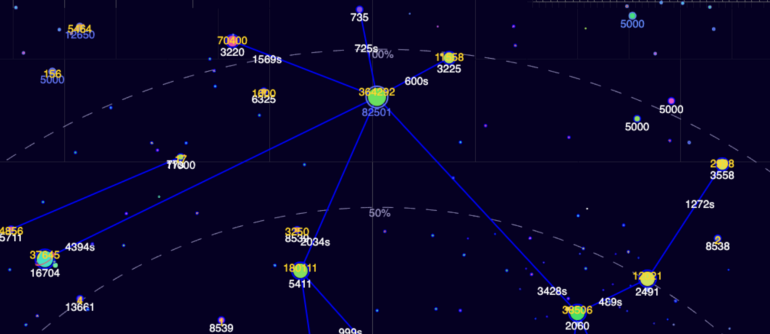

In the game of Dark Forest, players compete with one another for interplanetary territory. Players begin in complete darkness. A fog of war covers the universe surrounding their home planet. To explore, the browser makes use of players’ local computing power to compute a hash for each coordinate. Thereafter, that coordinate is revealed to the player and the map is slowly explored. Most coordinates contain nothing but empty space, but some contain planets, either uninhabited, or owned by other players. Once a planet is revealed, the browser can check on-chain to see if another player has staked a claim to the revealed rock, and see if other players try to take that planet.

Beginning with the one planet, a player (let’s call her Alice) publishes state transitions from her original planet to other planets. A state transition moves resources (population and silver) from an owned planet to the discovered planet, thereby colonizing a new planet, or attacking another player’s planet. Moving population between planets is limited by the origin planet’s range and population to move. Players can also upgrade their planets with silver — an in-game resource generated on certain planets that is used to purchase upgrades.

Planets gradually accumulate resources and, as players discover one another,

wars break out over high value planets. However, a player is not guaranteed to

know where an attack came from; only if the player has revealed the coordinates

of an attacking planet will they be able to see the red line indicative of an

enemy movement.

What makes the game possible is valid state transitions: how does the game move resources between planets, as on-chain data, without revealing the data, or committing invalid transitions?

What can we do without SNARKing?

Here’s the problem: Alice has a planet X with population N, and wants to send n people from X to planet Y, without revealing information about X, N, n, or Y to the rest of the world (state transitions on silver are in effect identical to population, so we’ll ignore them). Alice will have to prove:

- Ownership of X

- n < N

- A ship from planet X with n population has enough range to reach Y

Without SNARKs, Alice and company can still set their computers to the task of de-fogging the map: hashing each coordinate, looking for planets. There are two schemes that would allow Alice and company to play: 1) a centralized coordinator, or 2) a commit reveal scheme.

Centralized Coordinator Scheme

In the centralized coordinator scheme, Alice and company submit state transitions to a centralized coordinator with a god’s eye view. The coordinator can see X, N, n, and Y, and easily verify that each transition is valid. Most existing games rely on a centralized coordinator.

However, the centralized coordinator is a target for attacks and collusion, either of which could halt the game or reveal the universe to the attacking/colluding party. It’s not really a “Dark Forest” if someone has a universal floodlight, as is the norm with games on hosted game servers! As a cultural side note, companies who host games on servers assuage players’ fears by creating strong punishments for those caught cheating or attempting to cheat by hacking or other measures: players must trust the company’s promise to seek out and ban cheating players.

Commit-Reveal

In a commit-reveal scheme, each participant has some secret s that they want to hide from other players until some event occurs, or after a time delay T. Players publish the hash of their secret, H(s), and reveal the secret after the delay. Poker provides an example: players commit the hash of their cards at the beginning of the round, publishing H(s), and a player reveals the value of s if the hand does not terminate early.

In Dark Forest, players could agree on a time elapse to reveal their actions. If a player revealed an invalid action after the time delay, they could have some or all of their actions reverted, and optionally be punished in some other way (removal, temporary deactivation, etc). In each period, players would commit the hashes of their actions, H(a_1, …, a_k), and the game could proceed, except that no action would be publicly visible until after the period elapsed, along with X, N, n, and Y.

The core problem with a Commit-Reveal scheme is that information eventually must be revealed. Actions are only private up to the point of the next period, not for the entire duration of the game. This incentivizes a longer period of play, but a long period slows game pace, without resolving the fundamental issue of keeping game state private. Revealing concealed information at the end of each interval is fine for round-based games like poker, but not for games with a vast global state with a fog-of-war element (or for that matter, any application that would like to keep mutable state elements indefinitely concealed).

SNARKing through the Fog of Space

By applying a SNARK, Dark Forest players can submit proofs to the Dark Forest contract that X, N, n, and Y satisfy the necessary conditions. The Dark Forest contract verifies the proof, without ever having to know the values of X, N, n, and Y. Therefore, a player can submit moves and upgrade actions to the smart contract without allowing other players to know the contents of their actions.

This is almost perfect zero-knowledge. Other players are still able to see the number of transactions submitted by their rivals, and the block at which each transaction was included. From that on-chain information, a rival could determine when a player was most and least likely to be online, thereby receiving hints about when to attack. To eliminate even that information, Dark Forest would have to operate on a blockchain with shielded addresses or a privacy-enabled Layer 2.

It’s important to note that this applies to more than just games. Zero knowledge technology has broad application beyond Dark Forest. Experiments with zero knowledge systems are underway in voting systems, financial privacy, authentication without identification schemes, and even nuclear disarmament. In a broader context, the power of zero knowledge schemes is to conceal participants’ private information, while guaranteeing honest system-interaction. The Dark Forest zero knowledge game may serve as an approachable introduction to a field that has been respectfully referred to as “moon math”, in reference to its complexity. By bringing broader awareness to this technology, Dark Forest is a harbinger of novel zero-knowledge enabled experiments and applications, introducing the advantages of greater privacy and security in new ways.

first posted at the ZKPodcast blog